8 Auspicious Symbols of Tibetan Buddhism

Origin of symbolism in Tibetan Buddhism

Tibet is a gorgeous land of mysteries in China, spread out between India and the Himalayas in the South. The traditional nomadic culture was greatly influenced by the introduction of Buddhism from India, to the extent that most cultural achievements of Tibet are related to the Buddhist religion. Because of the prevalence of Tantra with its amusing custom of symbolism, it is no surprise that symbols and symbolic artifacts of all sorts are found in Tibet. Some of the symbols, however, originated in Tibet, or were given a specific meaning within the local culture.

8 Auspicious Symbols of Tibetan Buddhism

8 Auspicious Symbols of Tibetan Buddhism

Buddhism started as early as 6th BCE, when Siddhartha Gautama began preaching his teachings of suffering, enlightenment and rebirth in India. Siddhartha himself was antagonistic to accept images of himself, and used many diverse symbols to illustrate his teachings. There are eight different auspicious symbols of Buddhism, and many say that these signify the gifts that God made to the Buddha when he achieved nirvana.

Let us talk about these 8 different auspicious symbols of Buddhism.

The Parasol

The parasol, in other words, an umbrella is a traditional Indian symbol of royalty and protection from the raging heat of the tropical sun. The coolness of its shade signifies shield from the aching heat of suffering, temptation, hindrances, illnesses, and harmful forces. As a symbol of secular wealth, the greater the number of parasols carried in the entourage of a dignity, the higher his social rank would appear. Conventionally thirteen parasols defined the status of a king, and the early Indian Buddhists adopted this number as a symbol of the dominion of the Buddha as the ‘universal monarch’. Thirteen stacked umbrella-wheels form the conical spires of the various stupas that honored the main events of the Buddha’s life, or preserved his relics. This exercise was later applied to virtually all Tibetan Buddhist stupa designs. The great Indian teacher, Dipankara Atisha, who revived Buddhism in Tibet during the eleventh century, qualified for an entourage of thirteen parasols.

The Parasol

The Parasol

Patterns of Different Parasols

The emblematic Buddhist parasol is shaped from a long white or red sandalwood handle or axle-pole, which is embellished at its top with a small golden lotus, vase, and jewel filial. Over its domed frame is stretched white or yellow silk, and from the circular rim of this frame hangs a pleated silk frieze with many multi-coloured silk pendants and valances. A decorative golden crest-bar with makara-tail scrolling generally defines the parasol’s circular rim, and its hanging silk frieze may also be embellished with peacock feathers, hanging jewel chains, and yak-tail pendants.

Ceremonial silk parasol

Ceremonial silk parasol

A ceremonial silk parasol is traditionally around four feet in diameter, with a long axle-pole that enables it to be held at least three feet above the head. Square and octagonal parasols are also common, and large yellow or red silk parasols are frequently suspended above the throne of the reigning lama, or above the central divinity image in reclusive assembly halls. The white or yellow silk parasol is an ecclesiastic symbol of sovereignty, whilst a peacock feather parasol more specifically represents secular authority. The dome of the parasol represents wisdom, and its hanging silk pelmets the various methods of compassion. The white parasol that was presented to the Buddha by the serpent-spirits’ majesty symbolizes his aptitude to defend all beings from delusions and fears.

In Tibet, depending on their rank, various personages were entitled to different parasols, with religious heads being entitled to a silk one and secular rulers to a parasol with embroidered peacock feathers. Lofty personalities such as His Holiness the Dalai Lama are entitled to both, and in processions, first a peacock parasol and then a silk one is carried after him. When you visit Tibet, you will find these symbols in various festivals where such notables take part.

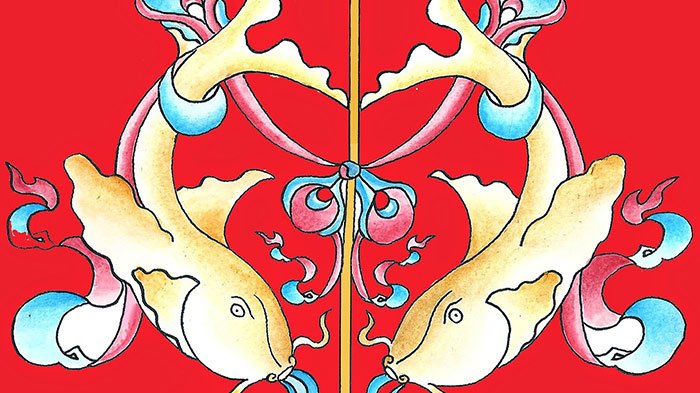

The Pair of Golden Fishes

In Sanskrit the pair of fishes is known as Matsyayugma, meaning ‘coupled fish’. This indicates their origin as an antique symbol of the two main sacred rivers of India, the Ganges and Yamuna. Symbolically these two holy rivers represent the lunar and solar channels or psychic nerves, which originate in the nostrils and carry the alternating rhythms of breath.

The Pair of Golden Fishes

The Pair of Golden Fishes

Symbolic Meaning of Symmetrical Fishes

In Buddhism the golden fishes represent happiness and impulsiveness, as they have complete liberty of movement in the water. They epitomize fertility and profusion, as they multiply very rapidly. They embody freedom from the fetters of caste and status, as they mingle and touch readily. Fish often swim in pairs, and in China a pair of fishes symbolize conjugal harmony and loyalty, with a brace of fishes being traditionally given as a wedding present.

A vessel stamped with the pair of golden fishes

A vessel stamped with the pair of golden fishes

The auspicious symbol of the two fishes that were offered to the Buddha was probably embellished in gold thread upon a piece of Benares silk. The sea in Tibetan Buddhism is associated with the world of suffering, known as the cycle of samsara. The Golden Fish have been said to signify courage and contentment as they swim spontaneously through the oceans without drowning, freely and instinctively, just as fish swim freely without fear through the water. The fishes symbolize happiness, for they have complete freedom in the water. They are traditionally drawn in the form of carp, which are commonly regarded in Asia as elegant due to their size, shape and longevity. If you visit Tibet, you can find this in various monasteries and areas where the message is conveyed.

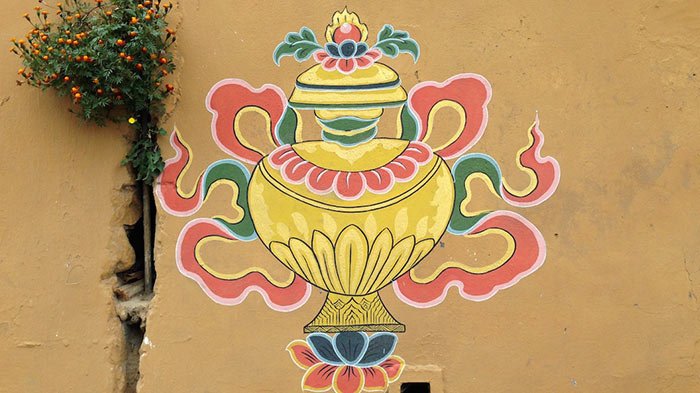

The Treasure Vase

The golden treasure vase, or ‘vase of inexhaustible treasures’, is exhibited upon the traditional Indian clay water pot. This pot is known as a kalasha or kumbha, with a flat base, round body, narrow neck, and fluted upper rim. This womb-like sacred kumbha is venerated in India at the great religious ‘pot festival’ of the Kumbh Mela. The treasure vase is mostly a representation of certain prosperity deities, including Jambhala, Vaishravana, and Vasudhara, where it often appears as a trait beneath their feet. One form of the wealth goddess Vasudhara stands upon a pair of horizontal treasure vases that spill an endless stream of jewels.

The Treasure Vase sign printed on the wall

The Treasure Vase sign printed on the wall

As the divine ‘vase of plenty’, it possesses the quality of natural display, because regardless of how much treasure is removed from the vase it remains perpetually full. The typical Tibetan treasure vase is represented as a highly ornate golden vase, with lotus-petal motifs radiating around its various sections. A single wish-granting gem, or a group of three gems, seals its upper rim as a symbol of the Three Jewels of the Buddha, dharma, and sangha.

Two Treasure Vase products

Two Treasure Vase products

The great treasure vase, as described in the Buddhist mandala offering, is shaped from gold and studded with an assembly of precious gems. A silk scarf from the god realm is tied around its neck, and its top is sealed with a wish-granting tree. The roots of this tree pervade the contained waters of longevity, amazingly creating all manner of treasures. Sealed treasure vases may be placed or buried at sacred geomantic locations, such as mountain passes, pilgrimage sites, springs, rivers, and oceans. Here their function is both to spread profusion to the milieu and to mollify the indigenous spirits who stand in these places. Besides the iconography of the Eight Auspicious Symbols, Treasure Vases filled with saffron water are found near the shrine offerings in a Tibetan Buddhist temple.

The Lotus

The Indian lotus, which grows from the dark watery swamp but is unblemished by it, is a major Buddhist symbol of purity and renunciation. It epitomizes the prospering of wholesome activities, which are performed with complete liberty from the liabilities of cyclic existence. The lotus seats upon the divine origin, the seats of gods. They are spotlessly conceived, characteristically perfect, and unquestionably pure in their body, speech, and mind. The deities manifest into cyclic existence, yet they are completely unadulterated by its defilements, emotional hindrances, and mental obscuration.

The Lotus symbol in Tibetan Buddhism

The Lotus symbol in Tibetan Buddhism

Surya, the Vedic sun god, holds a lotus in each of his hands, denoting the sun’s path across the heavens. Brahma, the Vedic god of creation, was born from a golden lotus that grew from the navel of Vishnu, like a lotus growing from an umbilical stem. Padmasambhava, the ‘lotus born’ tantric master who introduced Buddhism into Tibet, was similarly divinely conceived from an incredible lotus, which blossomed upon Dhanakosha Lake in the western Indian kingdom of Uddiyana.

Shape and Colors of Buddhist Lotus

The Buddhist lotus is described as having four, eight, sixteen, twenty-four, thirty-two, sixty-four, a hundred, or a thousand petals. These numbers emblematically correspond to the internal lotuses or chakras of the subtle body, and to the numerical components of the mandala. As a hand-held attribute the lotus is usually coloured pink or light red, with eight or sixteen petals. Lotus blossoms may also be coloured white, yellow, golden, blue, and black. The white or ‘edible lotus’ is an attribute of the Buddha Sikhin, and a sixteen-petaled white utpala lotus is held by White Tara. The yellow lotus and the golden lotus are generally known as padma, and the more common red or pink lotus is usually identified as the kamala.

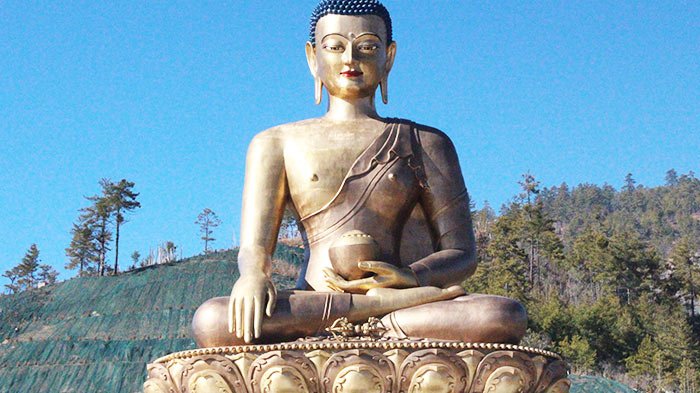

Lotus blossom as the Buddha base

Lotus blossom as the Buddha base

The roots of a lotus are in the mud, the stem grows up through the water, and the heavily scented flower lies above the water, reclining in the sunlight. This pattern of growth signifies the progress of the soul from the primordial mud of greediness, through the waters of experience, and into the bright sunshine of enlightenment. Though there are other water plants that bloom above the water, it is only the lotus which, owing to the strength of its stem, regularly rises eight to twelve inches above the surface. You can see Buddha sits on a lotus blossom in Tibet.

The Right-turning Conch Shell

The white conch shell, which spirals towards the right in a clockwise direction, is an ancient Indian attribute of the heroic gods, whose enormous conch shell horns proclaimed their valour and triumphs in war. Vishnu’s fire-emanating conch was named Panchajanya, meaning ‘possessing control over the five classes of beings’. Arjuna’s conch was known as Devadatta, meaning ‘god-given’, whose successful blast struck terror in the enemy. As a battle horn the conch is akin to the modern bugle, as an insignia of power, authority, and sovereignty. Its promising blast is believed to banish evil spirits, avert natural disasters, and scare away harmful creatures. In the Hindu tradition the Buddha is recognized as the ninth of Vishnu’s ten incarnations.

The Right-turning Conch Shell

The Right-turning Conch Shell

Conch Shell and Buddha’s teaching

The early Buddhists adopted it as a logo of the sovereignty of the Buddha’s teachings. Here the conch symbolizes his fearlessness in proclaiming the truth of the dharma, and his call to awaken and work for the benefit of others. One of the thirty- two major signs of the Buddha’s body is his deep and resonant conch-like voice, which resounds throughout the ten directions of space. In iconography the three conch-like curved lines on his throat embody this sign. As one of the eight auspicious symbols the white conch is usually depicted vertically, often with a silk ribbon threaded through its lower extremity. Its right spiral is indicated by the curve and aperture of its mouth, which faces towards the right. The conch may also appear as a horizontally positioned receptacle for aromatic liquids or perfumes . As a hand-held trait, symbolizing the decree of the Buddha dharma as the feature of speech, the conch is usually held in the left ‘wisdom’ hand of deities.

A Buddha-teaching thangka

A Buddha-teaching thangka

Today the conch is used in Tibetan Buddhism to call together religious assemblies. During the genuine practice of rituals, it is used both as a musical instrument and as a container for holy water. You will often come across it if you visit the holy areas of Tibet.

The endless or glorious knot

In its final development as a symmetrical Buddhist symbol the eternal knot or ‘lucky diagram’, which is described as ‘turning like a swastika’, was identified with the shrivatsa-svastika, since these parallel symbols were common to most early Indian traditions of the astamangala. The eternal, endless, or mystic knot is common to many ancient traditions, and became particularly ground-breaking in Islamic and Celtic designs. In China it is a symbol of longevity, continuity, love, and harmony. As a symbol of the Buddha’s mind the eternal knot epitomises the Buddha’s endless wisdom and compassion. As a symbol of the Buddha’s teachings it characterises the continuity of the ‘twelve links of dependent origination’, which triggers the reality of cyclic existence.

The endless knot yak bone pendant

The endless knot yak bone pendant

It depicts the nature of reality where everything is interrelated and only exists as part of a web of karma and its effect. Having no beginning or end, it also represents the infinite wisdom of the Buddha, and the union of empathy and knowledge. Also, it signifies the illusory character of time, and long life as it is endless. This is seen in almost every Buddhist monastery or temple in Tibet.

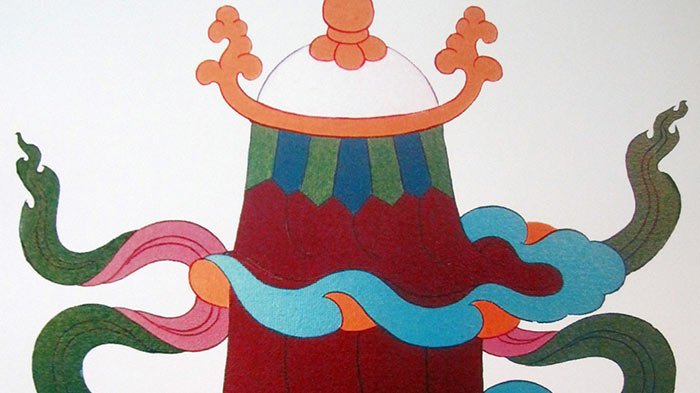

The Victory Banner

As a representation of the Buddha’s victory over the four maras, the early Buddhists adopted Kamadeva’s emblem of the crocodile-headed makaradhvaja, and four of these banners were established in the cardinal directions surrounding the illumination stupa of the Buddha. Similarly the gods elected to place a banner of victory on the summit of Mt Meru, to honour the Buddha as the ‘Conqueror’ who defeated the armies of Mara. This ‘victorious banner of the ten directions’ is described as having a jewelled pole, a crescent moon and sun finial, and a hanging triple band role of three coloured silks that are ornamented with the ‘three victorious creatures of harmony’.

The Victory Banner

The Victory Banner

Design of Victory Banner

Within the Tibetan tradition a list of eleven different forms of the victory banner is given to represent eleven specific methods for overpowering destructions. Many variations of the banner’s design can be seen on monastery and temple roofs, where four banners are commonly placed at the roof’s corners to symbolize the Buddha’s victory over the four maras. In its most traditional form the victory banner is fashioned as a cylindrical ensign mounted upon a long wooden axle-pole. The top of the banner takes the form of a small white parasol, which is surmounted by a central wish-granting gem.

Victory Banner on the roof of the monastery

Victory Banner on the roof of the monastery

This domed parasol is rimmed by an ornate golden crest-bar with makara-tailed ends, from which hangs a billowing yellow or white silk scarf. The cylindrical body of the banner is draped with overlapping vertical layers of multi-coloured silk valances and hanging jewels. A billowing silk apron with flowing ribbons adorns its base. The upper part of the cylinder is often decorated with a frieze of tiger-skin, symbolizing the Buddha’s victory over all anger and hostility. As a hand-held pennant the victory banner is an attribute of many deities, particularly those associated with wealth and power, such as Vaishravana, the Great Guardian King of the north. These can found in the roof tops of holy places in Tibet.

The Wheel

Buddhism assumed the wheel as the main insignia of the ‘wheel-turning’ Chakravartin or ‘universal monarch’, identifying this wheel as the dharmachakra or ‘wheel of dharma’ of the Buddha’s teachings. The Tibetan term for dharmachakra means the ‘wheel of transformation’ or spiritual change. The wheel’s rapid motion represents the fast spiritual transformation revealed in the Buddha’s teachings. The wheel’s comparison to the rotating weapon of the chakravartin represents its ability to cut through all obstacles and illusions.

The Wheel on the rooftop of Jokhang Temple

The Wheel on the rooftop of Jokhang Temple

The Buddha’s first discourse at the Deer Park in Sarnath, where he first taught the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Noble Path, is known as his ‘first turning of the wheel of dharma’. His subsequent great discourses at Rajghir and Shravasti are known as his second and third turnings of the wheel of dharma.

Major Components of the Wheel

The three components of the wheel - hub, spokes, and rim - symbolize the three aspects of the Buddhist teachings upon integrities, wisdom, and attentiveness. The central hub represents ethical discipline, which centres and stabilizes the mind. The sharp spokes represent wisdom or discriminating awareness, which cuts through ignorance. The rim represents meditative concentration, which both encompasses and facilitates the motion of the wheel. A wheel with a thousand spokes, which emanate like the rays of the sun, represents the thousand activities and teachings of the Buddhas. A wheel with eight spokes symbolizes the Buddha’s Eightfold Noble Path, and the transmission of these teachings towards the eight directions.

The wheel symbolic white-jade jewelry

The wheel symbolic white-jade jewelry

The auspicious wheel is labelled as being fashioned from pure gold obtained from the Jambud River of our ‘world continent’, Jambudvipa. It is traditionally depicted with eight spokes, and a central hub with three or four rotating ‘swirls of joy’, which spiral outward. When three swirls are shown in the central hub they represent the Three Jewels of the Buddha, dharma, and sangha, and victory over the three poisons of ignorance, desire, and aversion.

The bottom of the wheel usually rests upon a small lotus base

The bottom of the wheel usually rests upon a small lotus base

When four swirls are depicted they are usually colored to correspond to the four directions and elements, and symbolize the Buddha’s teachings upon the Four Noble Truths. The rim of the wheel may be depicted as a simple circular ring, often with small circular gold embellishments extending towards the eight directions. Alternatively, it may be depicted within an ornate pear-shaped surround, which is fashioned from scrolling gold embellishments with inset jewels. A silk ribbon is often draped behind the wheel’s rim, and the bottom of the wheel usually rests upon a small lotus base. This is visible in plenty of monasteries in Tibet such as the rooftop of Jokhang Temple and Drepung Monastery, etc.

Where do you find the 8 auspicious symbols in Tibet

These 8 auspicious symbols adorn all manner of sacred and secular Buddhist objects such as carved wooden furniture, metalwork, wall panels and carpets. They are also often drawn on the ground in sprinkled flour or color powders to welcome visiting religious leaders. Indeed, if you visit any religious or secular, such as marriage, ceremony, you are bound to witness the portrayal of these symbols which are believed to propitiate the surrounding and offer protection to the activity being undertaken.

The Lhasa-born prodigy used to study business overseas, and got his Bachelor of Business in Nepal and India before moving back to his homeland. With pure passion for life and unlimited love for Tibet, Kunga started his guide career as early as 1997.

Responsible, considerate, and humorous, he devoted his entire life to guiding and serving international tourists traveling in Tibet. As a legendary Tibetan travel guru with 20-year pro guide experience. Currently, he is working in Tibet Vista as the Tour Operating Director. Whenever our clients run into trouble, he is your first call and will offer prompt support.

.jpg)

0 Comment ON "8 Auspicious Symbols of Tibetan Buddhism"